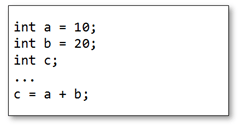

Simple question: Why does this code compile?

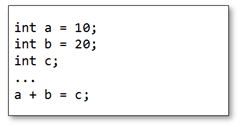

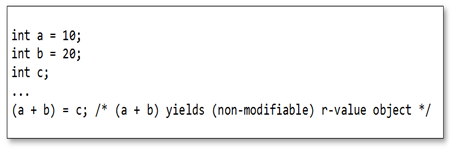

…and this code doesn’t?

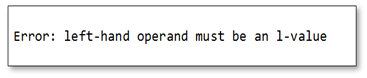

The compiler gives the following:

L-values

What is this ‘l-value’ thing? When (most of us) were taught C we were told an l-value is a value that can be placed on the left-hand-side of an assignment expression. However, that doesn’t give much of a clue as to what might constitute an l-value; so most of the time we resort to guessing and trial-and-error.

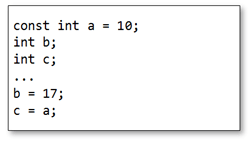

Basically, an l-value is a named object; which may be modifiable or non-modifiable. A named object is a region of memory you’ve given a symbolic name to variable (in human-speak: a variable). A literal has no name (it’s what we call a value-type) so that can’t be an l-value. A const variable is a non-modifiable l-value, but you can’t put them on the left-hand-side of an assignment. There fore our rule becomes:

Only modifiable l-values can go on the left-hand-side of an assignment statement.

R-values

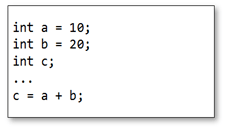

An r-value, if we take the traditional view, is a value that can go on the right-hand-side of an assignment. The following compiles fine:

By our definition, literals are r-values. But what about the variable a? We defined it as a (non-modifiable) l-value, so are l-values also r-values? We need a better definition for r-values:

An r-value is an un-named object; or, if you prefer, a temporary variable.

An r-value can never go on the left-hand-side of an assignment since it will not exist beyond the end of the statement it is created in.

(As an aside: C++ differentiates between modifiable and non-modifiable r-values. C doesn’t make this distinction and treats all r-values as non-modifiable)

Expressions

Where do r-values come from? C is an expression-based language. An expression is a collection of operands and operators that yields a value. In fact, even an operand on its own is considered an expression (which yields its value). The value yielded by an expression is an object (a temporary variable) – an r-value.

Type of an expression

If an r-value is an object (variable) it must – since C is a typed language – must have a type. The type of an expression is the type of its r-value.

It’s worth having a look at some examples.

In the case of an assignment expression (y = x) the result of the expression is the value of the left-hand-side after assignment; the type is the type of the left-hand side.

If the expression is a logical operator (a != b) the result is an integer (an ‘effective Boolean’) with a value 0 or 1.

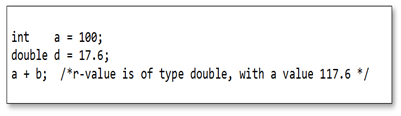

For mathematical expressions, the type of the expression is the same as the largest operand-type. So, for example:

C will promote, or convert, from smaller types to larger types automatically (if possible).

Finally, functions are considered r-values; with the type of the function being its return type. Thus, a function can never be placed on the left-hand-side of an assignment. There is a special-case exception to this: functions that take a pointer as a parameter, and then return that pointer as the return value, are considered l-values. For example:

(By the way, I don’t condone writing code like this!)

Back to the original question, then:

This compiles because c is a modifiable l-value; therefore can sit on the left-hand-side of an assignment. a + b is an expression that yields a (non-modifiable) r-value. Because of this, the code below cannot work:

And finally…

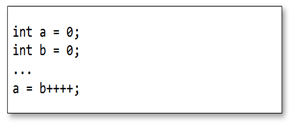

I’ll leave the following as an exercise for the reader (no prizes, though!)

Why does this compile:

…and this doesn’t:

- Practice makes perfect, part 3 – Idiomatic kata - February 27, 2020

- Practice makes perfect, part 2– foundation kata - February 13, 2020

- Practice makes perfect, part 1 – Code kata - January 30, 2020

Glennan is an embedded systems and software engineer with over 20 years experience, mostly in high-integrity systems for the defence and aerospace industry.

He specialises in C++, UML, software modelling, Systems Engineering and process development.

Oops, It seems both do not compile:

int main(void)

{

int a1 = 0;

int b1 = 0;

int a2 = 0;

int b2 = 0;

a1 = ++++b1;

a2 = b2++++;

return 0;

}

$ gcc test1.c

test1.c: In function ‘main’:

test1.c:10: error: lvalue required as increment operand

test1.c:11: error: lvalue required as increment operand

Got similar result on MSVC.

If there a typo in the blog entry:

Should

"An r-value can never go on the right-hand-side of an assignment since it will not exist beyond the end of the statement it is created in"

read

An r-value can never go on the left-hand-side of an assignment since it will not exist beyond the end of the statement it is created in

Tried again. You are right when it compiles as C++ code.

Good catch, Manish. You're a star.

Correct. This code (a1 = ++++b1) in C, but will compile in C++.

According to the C-99 Standard (ISO/IEC 9899:1999), Section 6.5.3.1 - The expression ++E is equivalent to (E += 1). By extension, ++++a1 should be (a1+=1)+=1 - which does compile.

In C++03 (ISO/IEC 14882:2003), Section 5.3.2 - The operand shall be an l-value... ...The value is the new value of the operand: it is an l-value.

Very interesting. Thanks for spotting that. If anything, it's yet another good justification for NOT writing code like ++++a1 🙂

@Glennan: "...it’s yet another good justification for NOT writing code like ++++a1."

Couldn't agree more.

Going back to the principles, it's a pity the standards' people, when revising and/or clarifyng the meanings of r-value and l-value, missed the opportunity to come up with more appropriate names for them. The r- and l- designations came quite obviously from "right" and "left" and this is (now) shown to be naive, at best.

"Thus, a function can never be placed on the right-hand-side of an assignment."

But, we can have function on right hand side of an assignment

int i;

i =sum(10+20);

typo

int i;

i =sum(10 ,20);

I suppose the @Param comment is correct.

Is the sentence

> "Thus, a function can never be placed on the right-hand-side of an assignment"

should be read as

>"Thus, a function can never be placed on the left-hand-side of an assignment"

?

Thanks.